How do we know if we are improving? UN-Nutrition launched an online survey to capture the state of inter-agency collaboration on nutrition at country level between January and December 2021 – the first full year as UN-Nutrition. The results would help to establish a baseline against which progress could be measured over time and to orient future support to countries. UN-Nutrition focal points and facilitators who contribute to these collective activities completed the survey, submitting one response per country. As a result, this reporting exercise in and of itself provided a rallying point for nutrition colleagues from various UN agencies. Regional offices disseminated the survey to country focal points, which increased the reach, particularly to those countries outside the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Movement. Overall, 44 countries [1] out of 101 countries responded to the survey. A sample size of 44 will not allow statistical significance. Nonetheless, the statistics and trends reported here do provide some indication of how UN agencies are collaborating on nutrition, bringing interesting insights to the table.

The findings of this baseline assessment are based on these 44 responses. Nearly 70% of countries that complied (30 [2] out of 44) are part of the SUN Movement, which is not surprising in view of their historical ties to the UN Network for SUN, one of the UN-Nutrition’s predecessors.

Structure

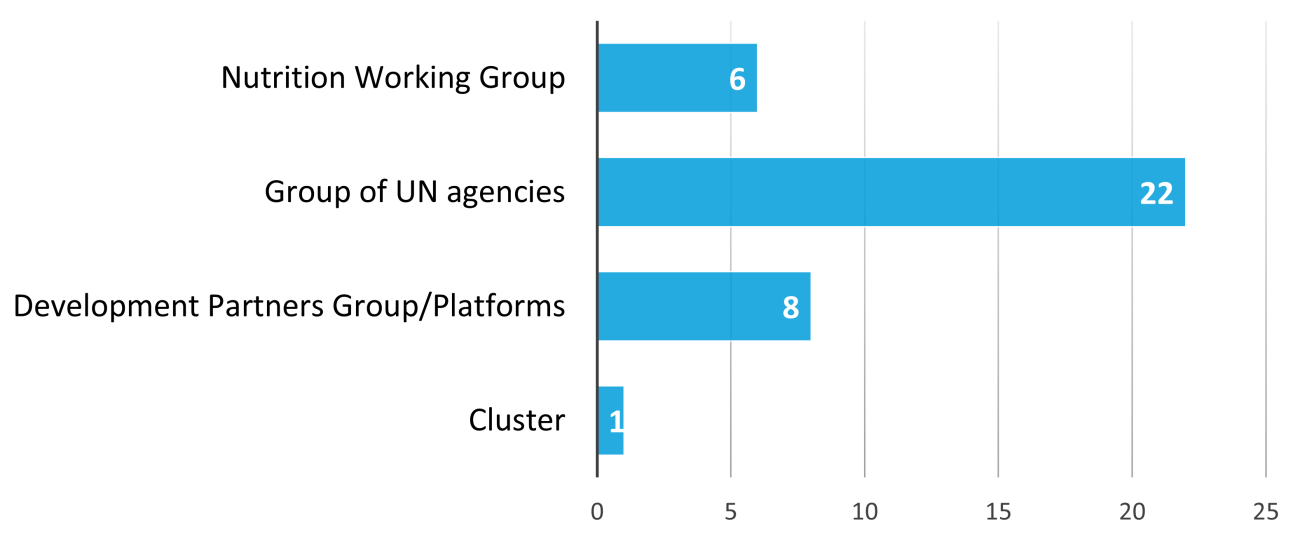

Most countries surveyed (40 out of 44) had a coordination mechanism in place through which UN actors collaborate on nutrition with the exception of the Central African Republic (CAR), the State of Libya, the United Mexican States and the Republic of Nicaragua. Of those structures, 22 (55%) were exclusively comprised of UN members and 18 (45%) solely focused on nutrition. We know that the actual number is higher, as nutrition coordination structures do exist in other countries that did not complete the survey (e.g. Lesotho, Liberia). In cases where there was no distinct nutrition coordination structure, nutrition issues were discussed through broader platforms, such as Development Partners Groups (e.g. Egypt, Guatemala, Togo, Kyrgyzstan, Lao PDR) and a joint Food Security and Nutrition Cluster as reported by Colombia. In some cases, there is an explicit reference to food systems in those broader groups (23 countries), providing a formal entry point for dialogue about nutrition vis-à-vis diets. These findings show that UN-Nutrition can take different forms in different countries without necessarily formalizing a discrete group.

Figure 1. Type of coordination structure through which UN actors collaborated on nutrition (2021)

Membership and stewardship

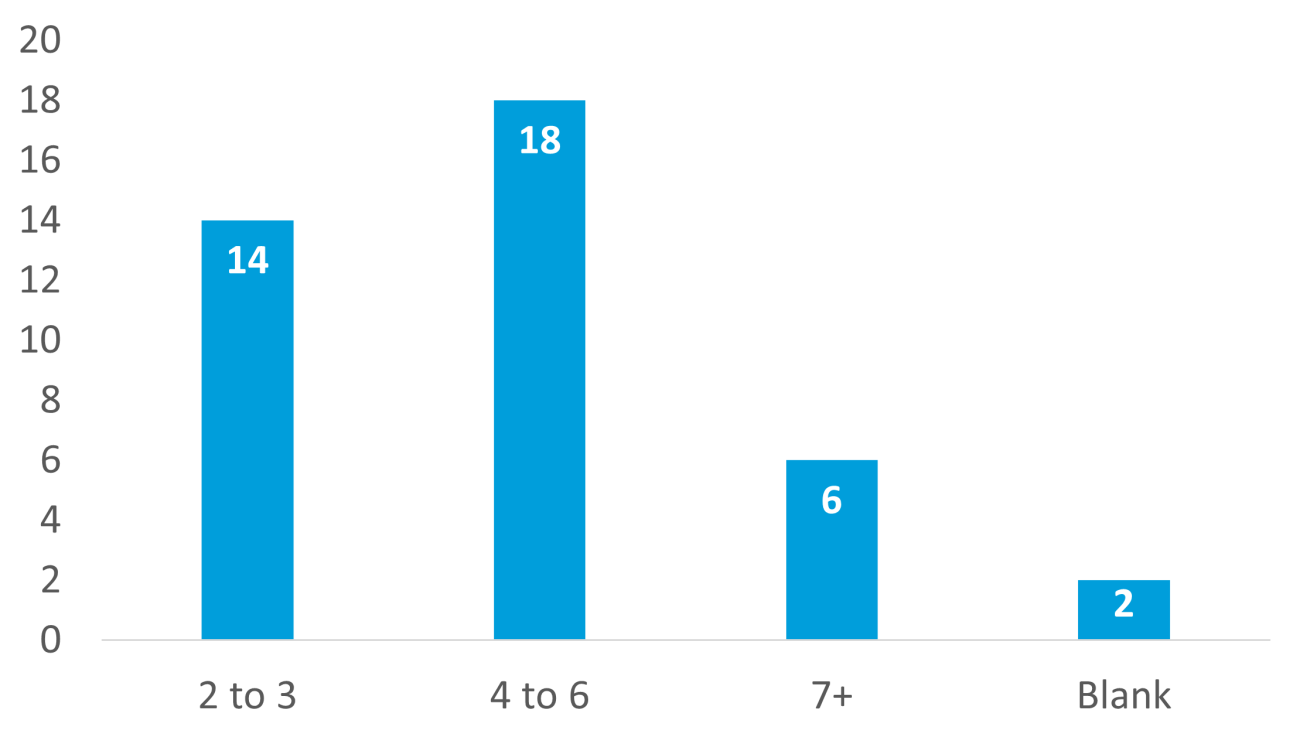

The data shows two clear trends in terms of participation. By far, four UN agencies most frequently participate in such country-level collaboration platforms: FAO (36 countries); UNICEF (36 countries); WFP (30 countries); and WHO (29 countries). Additionally, fourteen other agencies were involved in at least one country. The findings also provide insights about membership size in a given country, indicating that UN representation in the coordination structure typically ranges between two and six agencies (32 countries). This not only illustrates that multiple UN entities are engaged in the nutrition arena at country level, but it also highlights the need to coordinate between them to foster coherence and synergies.

Figure 2. Number of UN entities participating in the coordination structure

The findings also indicate that a large proportion of countries (28 out of 44) have identified a UN representative to lead collective nutrition activity, most often from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Furthermore, 82% of these countries (23 out of 28) had also engaged with the United Nations Resident Coordinator (UNRC) or humanitarian coordinator. Nine additional countries reported having engaged the UNRC in the nutrition agenda during the reporting period, amounting to circa 73% (32) of the countries surveyed overall. This demonstrates the high level of stewardship on nutrition within the UN System and is likely, in part, the fruits of ongoing efforts to leverage UNRCs as nutrition champions. On the other hand, ten countries indicated they did not involve the UNRC, which could indicate a need for action to improve coordination.

Zooming in

Another key metric was the overall perceived progress that each country had achieved over the past year. According to the baseline data, 64% of countries (28 out of 44) reported having improved nutrition coordination within UN entities in 2021. This trend was observed in all major regions (Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as the Middle East) and many countries (20) where the UNRC or Humanitarian Coordinator was engaged in the nutrition agenda, suggesting that these senior figures can be crucial for catalysing joint nutrition action.

What does progress look like in concrete terms? The survey explored various dimensions of joint activity from planning to advocacy, assessment and programming. In terms of planning, the majority of countries (66%) had a collective UN nutrition strategy or agenda put in place, including one country where there was no coordination structure (Mexico). This serves as a reminder that UN entities can also collaborate on nutrition in the absence of formal coordination structures. Nevertheless, the existence of these joint strategies/agendas may help pave the way for increased coherence and synergy among UN entities to help countries fight malnutrition.

Furthermore, 41 countries (93%) had reflected a multi-sectoral approach to nutrition in United Nations cooperation frameworks (e.g. United Nations Sustainable Development Cooperation Frameworks [UNSDCFs], United Nations Development Assistance Frameworks [UNDAFs], Humanitarian Response Plans) during the last two years. It is essential that nutrition is intrinsically integrated within the country UNSDCF/UNDAF in order for it to be addressed in a multi-faceted way. Various approaches for ‘nutrition mainstreaming’ in the UNSDCF/UNDAF were pursued although the most common trend was to integrate it under specific outcomes (28 countries). Seven of those countries had also reflected nutrition at the pillar level (e.g. Afghanistan, Libya, Sierra Leone, Tajikistan) whereas an additional seven countries had only included it at the pillar level (e.g. Cameroon, CAR, Guatemala, Niger). In Cameroon, the UN-Nutrition group recognized the significance of proper nutrition as a driving force for human capital development and ensured its inclusion in the UNSDCF. Marc Nene, Chief of Nutrition at the country UNICEF office, who convenes the group, explains that

“under the strategic priority [pillar] focusing on quality, inclusive, and equitable human and social development, the UN-Nutrition technical group proposed tailored outputs to address all forms of malnutrition across various stages of life.”

The baseline findings also revealed that four countries positioned nutrition as a crosscutting area (Egypt, Malawi, Papua New Guinea and the Republic of South Sudan), which may likely help leverage the potential of nutrition to drive sustainable development.

The Republic of South Sudan (herein South Sudan) was one of the countries that reported making overall progress in 2021, with as many as sixteen UN agencies collaborating on nutrition. These include: FAO; IFAD; IOM; OCHA; UNAIDS; UNDP; UNESCO; UNFPA; UN-Habitat; UNHCR; UNICEF; UNMAS; UNOPS; UN-Women; WFP; and WHO. In an effort to examine factors underpinning its success, it was found to be among the countries that reported having a specific UN coordination platform for nutrition, a UN collective nutrition strategy, agenda or workplan in place, and engaging with the UNRC or Humanitarian Coordinator. Furthermore, nutrition was reflected as a cross-cutting area in the UNSDCF/UNDAF in South Sudan and the UN-Nutrition group had also carried out joint assessments, joint advocacy and joint programmes. This positions UN-Nutrition South Sudan as a high-performer and potentially a gold standard for inter-agency collaboration that other countries could potentially learn from or emulate.

Going beyond joint planning

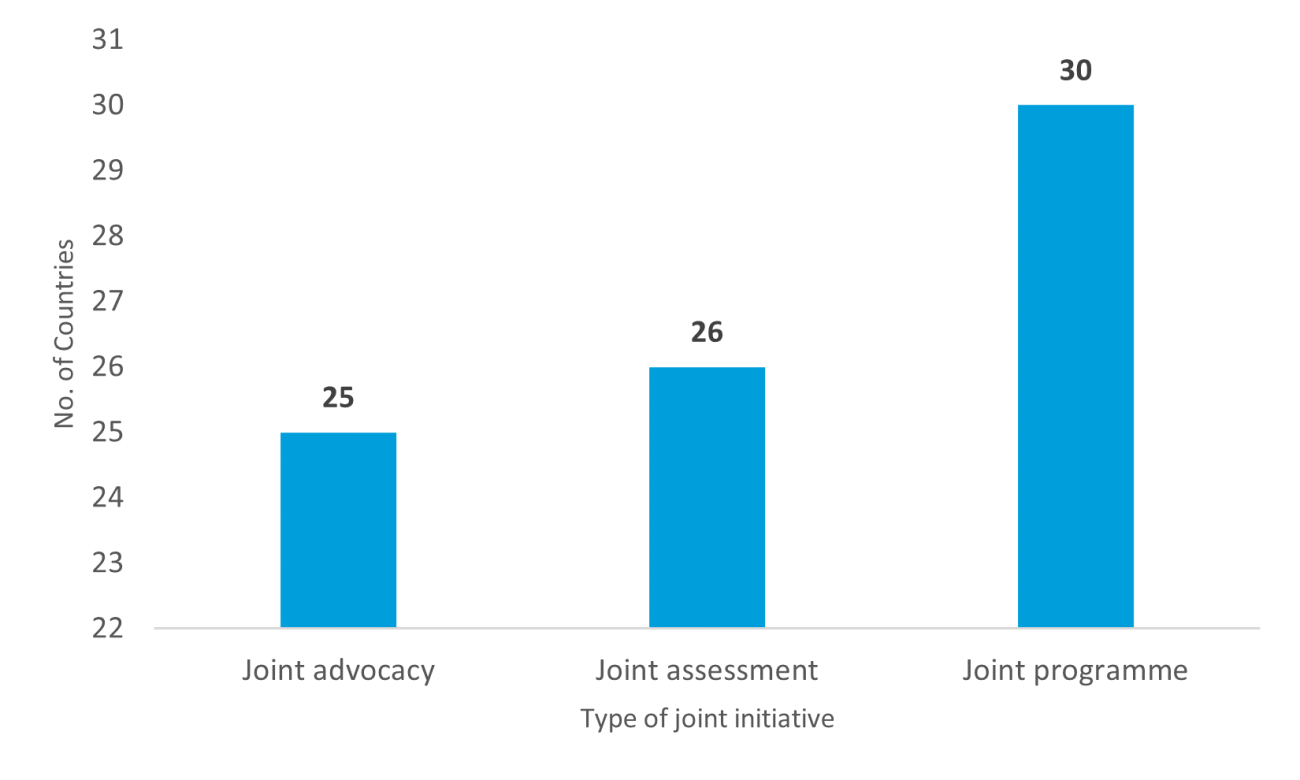

In 2021, an impressive 89% of countries were shown to have UN joint nutrition initiatives (advocacy, assessment/evaluation and/or programming) in place and being carried out by two or more UN agencies. Approximately half (52%) of these were undertaken in both humanitarian and development implementation settings. Piyali Mustaphi of UNICEF explains how

“collaborative advocacy across UN partners was a key factor contributing to the Government of Bangladesh committing to improving nutrition on the international stage, at both the Nutrition for Growth and Food Systems Summit.”

Piyali is the Chief of Nutrition in the UNICEF country office and also leads the UN-Nutrition group in Bangladesh. Similarly, UN-Nutrition Member Agencies in the Sudan played a leading role to advocate for and technically support the development of fourteen endorsed Nutrition for Growth (N4G) commitments, utilizing the expertise across sectors to ensure multi-system commitments. This was a key step in raising the visibility and importance of nutrition among key nutrition-relevant ministries and other stakeholders. Furthermore, fourteen countries (e.g. Bangladesh, Guatemala, Kyrgyzstan, Mali, Rwanda, Senegal, Zimbabwe) had joint initiatives in all three domains. Interestingly enough, all fourteen had reported that coordination structures were in place, eight of which were devoted to nutrition. This further attests to the inter-agency cooperation within countries across regions to leverage the collective strength of UN agencies in working towards the common goal. It also suggests that the presence of a coordination structure can be an enabling factor for countries to carry out joint nutrition activity. However, not too many countries reported having a joint work plan for nutrition. While there are various joint initiatives, and sometimes, a joint work plan, there is still scope to step up joint action, including joint programming.

Figure 3. A glimpse at different types of joint UN initiatives pursued at country level (2021)

SUN snapshot

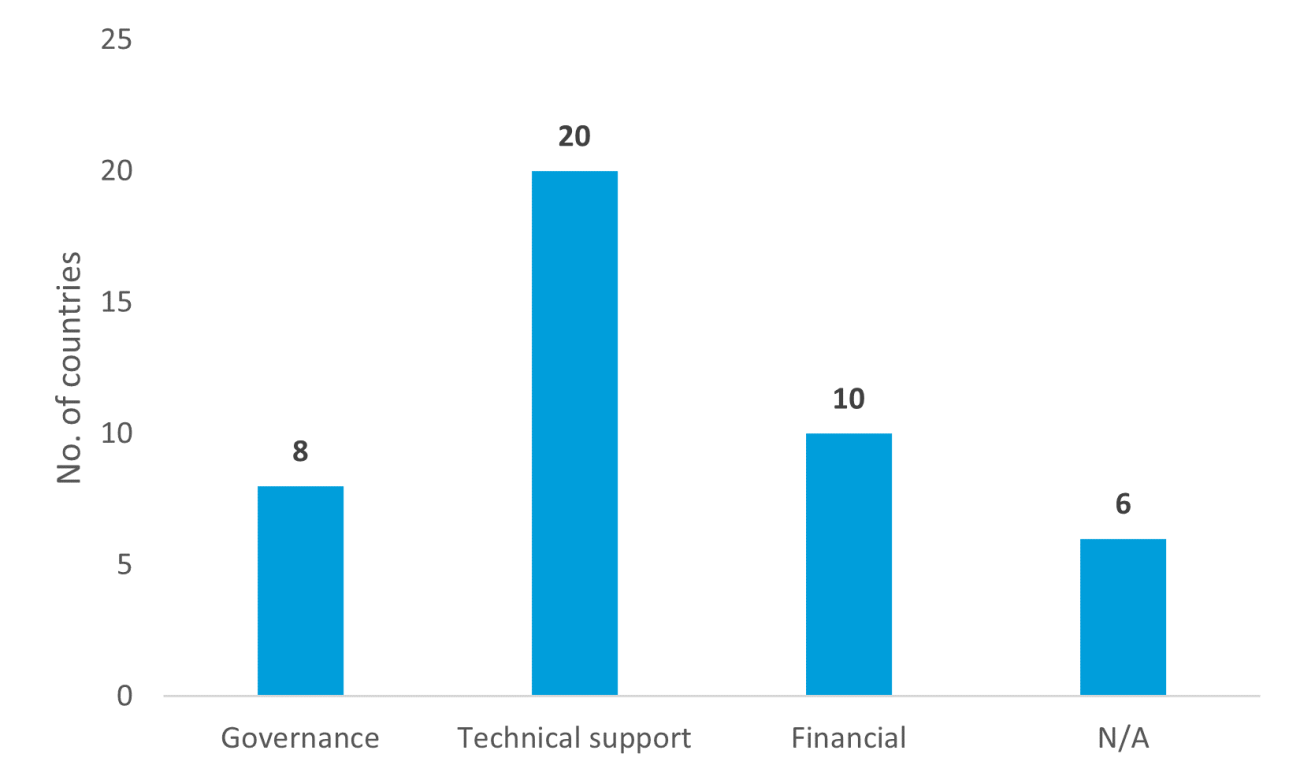

All thirty SUN countries that responded to the survey had supported SUN structures in the country (beyond UN-Nutrition), including the SUN Country Coordinator and other government authorities during the reporting period. This took the form of technical, financial and governance support, with the former being most commonly reported (20 countries).

Different combinations of support were provided in some cases. For example, support spanned across all three dimensions in four countries (Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Niger and the Sudan). UN-Nutrition’s support was pivotal in the Sudan during this delicate period. Due to the political situation and the COVID-19 pandemic, the work of the SUN Movement with the exception of UN-Nutrition was paused during 2020−2021. Through joint advocacy from UN-Nutrition members and collective support, the SUN Secretariat was recapacitated, a 5-year SUN roadmap developed and the civil society, business, and research and academia networks were revitalized with the support of WHO, WFP and UNICEF respectively, including the development of new TORs in line with the SUN Movement global strategy 3.0. However, the fight against malnutrition is far from over in these countries and further support is needed to help them achieve the WHA nutrition targets. For example, Niger has made limited progress towards achieving those targets and the other three countries are ‘on course’ for just two of the six targets according to the 2022 Global Nutrition Report.

Notwithstanding, inadequate coordination was indicated as both the most common challenge (20 countries) and among the top priorities (23 countries) for supporting government to improve nutrition outcomes. Insufficient funds followed as the second most common challenge. However, just three countries, all in West Africa, included it among their top priorities for the following year. A critical mass of countries (25) also identified assistance with the joint workplan as another priority for the common nutrition agenda, including several countries that have a common UN nutrition strategy or agenda in place.

Conclusion

The UN-Nutrition baseline assessment sheds light on how UN entities are collaborating on nutrition in countries, including the extent to which this area has been integrated into UN country portfolios, as of 31 December 2021. The results, while indicative, show promising signs that Member Agencies are working to align and consolidate their efforts right down to programming in several countries. They also illustrate the diversity of coordination modalities and membership ‘’on the ground,’’ as well as the challenges UN colleagues are facing in the quest to “deliver as one” on nutrition. In the immediate term, these insights are crucial for helping UN-Nutrition pivot to meet country needs. For example, efforts could be taken to further explore the situation in the four countries that did not have a coordination structure in place and countries that cited improving coordination and assistance with devising joint workplans among their top priorities. They are useful for determining whether and where improvement is/is not being made as UN-Nutrition matures as a collective, cognizant that no single UN entity can end hunger and malnutrition in the world.

With regard to strengthening the UN-Nutrition networking, countries are typically requesting how to strengthen inter-agency work, such as joint work plan, advocacy or higher-level engagement from the UNRC in the nutrition agenda. Funding and resource mobilization are also major concerns, with eleven requests made in this regard. Several UN agencies have inquired about potential support for funding, resource mobilization and joint advocacy for nutrition. Additionally, two countries would benefit from support in inter-agency coordination for the Global Action Plan (GAP) on wasting. Finally, UN agencies expressed the need for better collaboration with regard to national multi-sectoral strategies in nine countries and four countries have indicated their desire to strengthen coordination among government-level multi-sectoral platforms. This is a starting point in the road to improvement and interesting food for thought for UN-Nutrition colleagues working at all levels.

Endnotes

[1] These include: the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan; the Republic of Angola; the People's Republic of Bangladesh; the Republic of Cameroon (herein Cameroon); the Central African Republic; the Republic of Chile; the Republic of Colombia; the Republic of the Congo; the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire; the Arab Republic of Egypt (herein Egypt); the Republic of El Salvador; the Republic of Ghana; the Republic of Guatemala (herein Guatemala); the Republic of Haiti; the Republic of India (herein India); Jamaica; the Kyrgyz Republic (herein Kyrgyzstan); the Lao People's Democratic Republic (herein Lao PDR); the State of Libya; the Republic of Madagascar; the Republic of Malawi (herein Malawi); the Republic of Mali (herein Mali); the Islamic Republic of Mauritania; the United Mexican States; the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; the Republic of Nicaragua; the Republic of the Niger (herein Niger); the Republic of Panama; the Independent State of Papua New Guinea (herein Papua New Guinea); the Republic of Paraguay; the Republic of Rwanda (herein Rwanda); the Republic of Senegal (herein Senegal); the Republic of Sierra Leone (herein Sierra Leone); the Syrian Arab Republic; the Republic of South Sudan; Palestine; the Republic of the Sudan (herein the Sudan); the Republic of Tajikistan (herein Tajikistan); the Togolese Republic (herein Togo); the Republic of Tunisia; the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam; the Republic of Yemen; the Republic of Zambia (herein Zambia); and the Republic of Zimbabwe (Zimbabwe).

[2] India was not counted as part of these countries since it has not joined the SUN Movement at that national level. With that said, four of its states have done so.