Introduction

As the nutrition community reflects on the global nutrition targets post-2025, including the integration of possible process indicators, the UN-Nutrition mapping tool takes on increasing importance. Why? It’s rather simple. How can we expect to achieve such targets if service delivery is limited? The aggregated coverage data that this mapping exercise yields can help government-led nutrition coordination platforms, such as Sierra Leone’s SUN[1] Secretariat, identify where there are coverage gaps amidst the myriad of nutrition stakeholders and provide indications of where to direct investment (including domestic resources) for advancing nutrition action. This article provides a snapshot of how the UN-Nutrition mapping tool is helping actors in Sierra Leone track intervention coverage over time and inform related decision-making.

Finding order in the crowded nutrition landscape

Following the successful mapping undertaken in 2018–19,[2] the national SUN Secretariat in Sierra Leone embarked on a second iteration in August 2023 with support from the UN-Nutrition Secretariat. Round 2 aimed not only to measure intervention coverage of 30 core nutrition actions (five more with respect to the previous round), but also to see how such coverage had evolved four years and one pandemic later. The actions were selected through consultations with the national SUN Secretariat, 16 government ministries and departments, seven United Nations agencies,[3] 14 private sector actors and a plethora of civil society organizations. They cover a subset of the actions included in the national nutrition plan (2019–2025),[4] enabling the government to monitor the implementation status of that guiding framework at least in part. The actions straddle six sectors[5] in addition to the cross-cutting area of women’s empowerment and the environment. Furthermore, they encompass both nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive actions, ranging from the treatment of acute malnutrition to the provision of training on community gardens and the promotion of open defecation-free villages. As foreseen by the mapping methodology, the 200-plus stakeholders included were classified into four groups (responsible ministry, implementer, catalyst[6] and donor) depending on their role in a given nutrition intervention in order to minimize the risk of double-counting.

Moving the needle

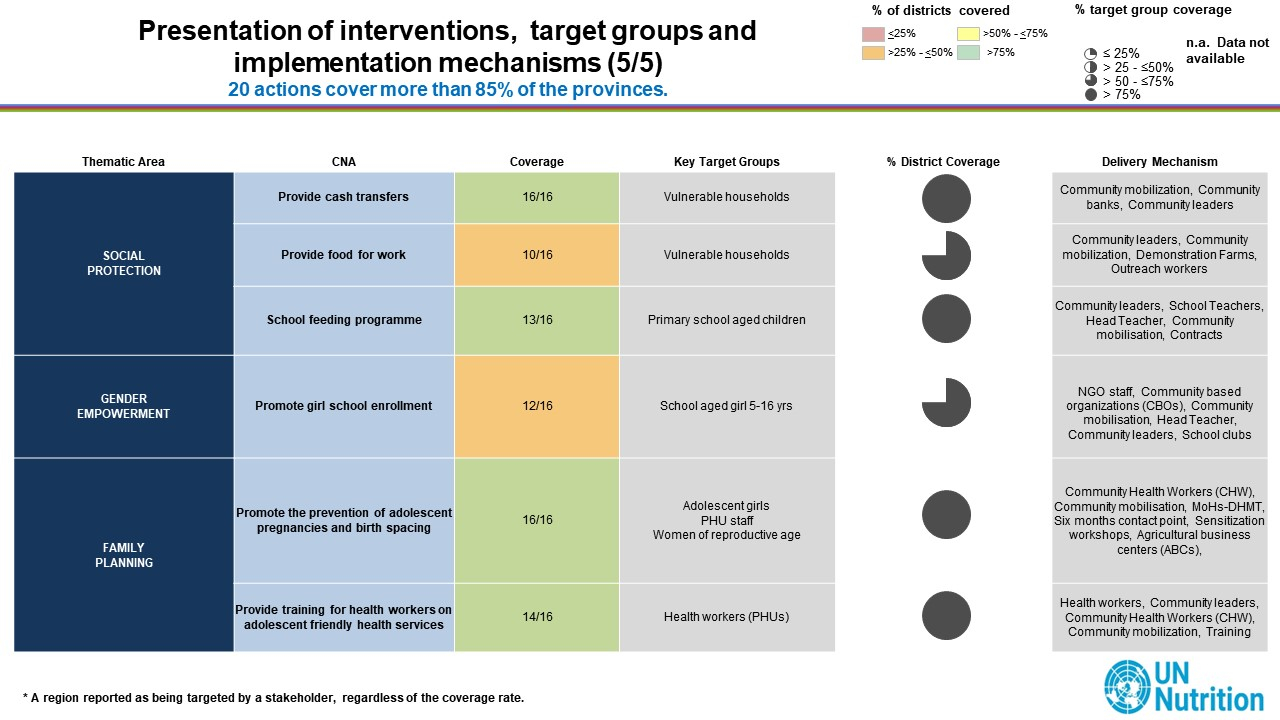

“Through comprehensive mapping, we can pinpoint specific regions or populations requiring more attention, ensuring our efforts are focused and effective, and enabling better resource allocation and collaboration among stakeholders,” stated Edith Rogers the UN-Nutrition facilitator in Sierra Leone and FAO nutrition focal point. The exercise estimates both geographic and population coverage for each action mapped. For example, coverage was lowest for supplementary feeding, targeting vulnerable households during emergencies/disasters, which reached just one of several affected districts and less than 25% of targeted households in Round 2. This was surprising given that the intervention had reached all four provinces according to the results of the previous mapping in 2018–19. While the provincial-level results from Round 1 may have masked disparities among the districts, they still indicate that the action covered a minimum of four districts compared to the single district with coverage observed in Round 2. Higher coverage was observed for other forms of food assistance, such as cash transfers and food for work, which reached vulnerable households in 16 and 10 districts respectively. Furthermore, approximately half (17) of the interventions mapped covered all sixteen districts while 23 were estimated as covering over 75% of the targeted population in the recent mapping.[7] This is encouraging overall. However, direct comparisons in coverage cannot be made between the two rounds since the initial exercise reported such figures by province only. The increased granularity of the coverage data in this latest round of mapping gives more insight into where corrective measures and further analysis are warranted (e.g. supplementary feeding for vulnerable households in emergency settings).

Mariama Bah, a nutrition specialist who works at the UNICEF country office, indicated that “UNICEF will leverage the findings from the mapping exercise to identify and address coverage gaps in nutrition services/interventions, direct resources more efficiently, and strengthen government-led nutrition coordination in Sierra Leone.” This includes essential nutrition services aimed at preventing and treating child malnutrition like community-based counseling, support and services to improve feeding and care practices in early childhood, especially for those living in severe child food poverty.

Towards increased ownership and efficiency

In addition to the utility of the findings, the mapping galvanizes diverse stakeholders and prompts action-oriented multisectoral dialogue. Over 65 stakeholders attended the mapping validation workshop last April where the preliminary results were presented, and they saw how their efforts contribute to a greater whole. This, in turn, fosters a culture of inclusivity and collaboration. Edith has witnessed a deepening sense of ownership among nutrition stakeholders. “Whether it’s local communities, civil society, academia, private sector actors or government agencies, there is a growing recognition of the collective responsibility they share for the nation’s future,” she explained. This holistic view is also helping the national SUN Secretariat see how to better align nutrition actions pursued by various stakeholders. “The stakeholder mapping is working because we are putting in place modalities to make sure that we know where everybody is working… to avoid duplication, to avoid wastage,” said Nenebah Jalloh, the National SUN Coordinator, based in the Vice President’s Office. In this sense, the mapping is “a tool that informs prioritization of needs with available resources,” said Francess Boima, a nutritionist at WFP.

Private sector

A new section on the private sector was introduced through this second wave of mapping in Sierra Leone. This component includes data on major private sector actors, who are engaged in different facets of food systems from food processing companies (e.g. Bennimix Food Company Limited, Lion Foods and Beverages) to the Ogofarm Farmers Development and Agribusiness Enterprise and related labour unions (e.g. the Sierra Leone Artisanal Fishermen Union). The data was gathered through interviews and goes beyond the 3Ws (who, what, where) of the classic mapping, enabling a ‘light-touch’ analysis of how these actors support the national nutrition agenda. The decision to integrate this component was largely due to the mounting momentum around food systems transformation and an interest in better understanding private sector nutrition-related activity. It explored five dimensions, starting with an overview of their respective business values and missions. It also examined the nutrition focus of their activities, both workplace/workforce and non-workplace commitments to nutrition, as well as their alignment with national nutrition priorities.

One of the main takeaways from this component of the mapping is that the companies surveyed are united in the goal to make Sierra Leone self-sufficient in food production while simultaneously addressing malnutrition-related issues. According to their responses, they mainly contribute to good nutrition by promoting diverse crops for balanced diets or fortifying food products with vitamins and minerals (e.g. the production of food blends). A considerable proportion of the companies noted their dedication to environmental sustainability, although a smaller number of them reported their business activities were aligned to government policies. Those private sector actors that were particularly attuned to and compliant with related government policy and regulations were engaged in the fishing industry. In terms of nutrition-friendly workplace metrics, half of the business entities have designated areas for breastfeeding, while 64% offer some degree of maternity protection and have existing health and wellness policies, respectively. Paternity leave is granted by just one company, pointing to a need for more gender-transformative nutrition actions. Some companies reported innovative partnerships with WFP and non-governmental organizations. For example, one company sells local fish products at discounted prices to school feeding programmes. While these findings provide some indication of responsible and nutrition-smart business practices, they also highlight that there is room for improvement. Furthermore, the mapping did not evaluate the extent to which compliance to such policies and practices are enforced. Additional details are included in the recently released Sierra Leone mapping report.

Challenges and limitations

Sierra Leone’s mapping journey was not without obstacles. Among the challenges encountered along the way were outdated data, busy schedules of the stakeholders mapped and limited access to data, such as census data from government authorities that is required to calculate population coverage. In other instances, incorrect information was submitted, necessitating follow-up calls to ensure accuracy (e.g. avoid double-counting). There were also delays, as organizations often took longer than expected to submit their data. “However, in the face of these challenges, stakeholders have also discovered opportunities for innovation and collaboration,” stated Zack Knechtel of the UN-Nutrition Secretariat, who provides backstopping support to countries on the exercise.

Conclusion

The mapping exercise is helping to improve nutrition coordination in Sierra Leone by providing an overview of the nutrition stakeholders, where they are working and estimated coverage of beneficiaries for selected nutrition actions. “It provides strategic reflection around nutrition actions, explaining the multi-sectoral approaches in addressing malnutrition in Sierra Leone, while giving us a broad sense of how our work is crucial to improving nutrition outcomes and sustainable development goals through partnership,” said Francess at WFP. Mariama of UNICEF explained that “the results have spurred discussions on joint UN programming and new partnerships aimed at enhancing the delivery of nutrition interventions.” While stakeholders in Sierra Leone, generally found the mapping to be useful, the results of this exercise should be interpreted as ‘indicative and directional’ given the voluntary and self-reported nature of the data on which it is based, and the limited number of actions included. Moreover, the mapping complements other tools and analytical exercises, including those of UN-Nutrition Member Agencies like budget and expenditure tracking.

Looking ahead, stakeholders plan to make the food systems link more explicit in successive iterations of the exercise. For example, nutrition stakeholders may revisit the suite of actions mapped, integrating others that are included in the national food systems pathway to reinforce nutrition in those parallel efforts. In the meantime, the national SUN Secretariat and its partners recognize the value of having the aggregated intervention coverage data generated by the mapping and the subsequent sensitization it has prompted on the roles and contributions of the various stakeholders. Further efforts are needed to deliver nutrition interventions at scale. With over 240 actors in the nutrition landscape,[8] these types of coordination tools are imperative for maximizing the impact of efforts. It is otherwise difficult to hope for more than diluted fragmentation and the global nutrition targets risk being little more than aspirational.

Notes and references

[1] SUN stands for Scaling Up Nutrition.

[2] To view the findings of the 2019 mapping exercise, visit https://bit.ly/4bUw7tr.

[3] The seven participating UN agencies are: (the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD); the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA); the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Programme (WFP); and the World Health Organization (WHO).

[4] This refers to the Multi-sector Strategic Plan to reduce Malnutrition in Sierra Leone (2019-2025) available at https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC212092.

[5] These include agriculture, education, finance, health, social protection, and water and sanitation.

[6] For the purpose of this mapping exercise, a catalyst is defined as “partners who provide coordination, M&E and/or technical assistance to the nutrition actions being mapped.”

[7] Definitions of the interventions mapped as well as their respective target groups are outlined in the 2024 Sierra Leone mapping report available at https://bit.ly/46I3LB9.

[8] Refer to the mapping report for the full list of stakeholders covered in Round 2 of the mapping exercise in Sierra Leone.